Actor and author Courtney B. Vance shares his experiences, urges Black men to seek mental health care.

In his keynote address at the African American Alumni Committee 2024 Symposium, Vance discussed how to move past suffering and into action.

By Sarah Steimer

“We're very good at suffering,” actor and author Courtney B. Vance told his audience on February 17, part of the African American Alumni Committee 2024 Symposium. “And we’ll stay there to suffer through whatever, because it's too much work to actually get some help. But you just have to get ready for the journey for yourself, because it's about us. It's about finding your way to you.”

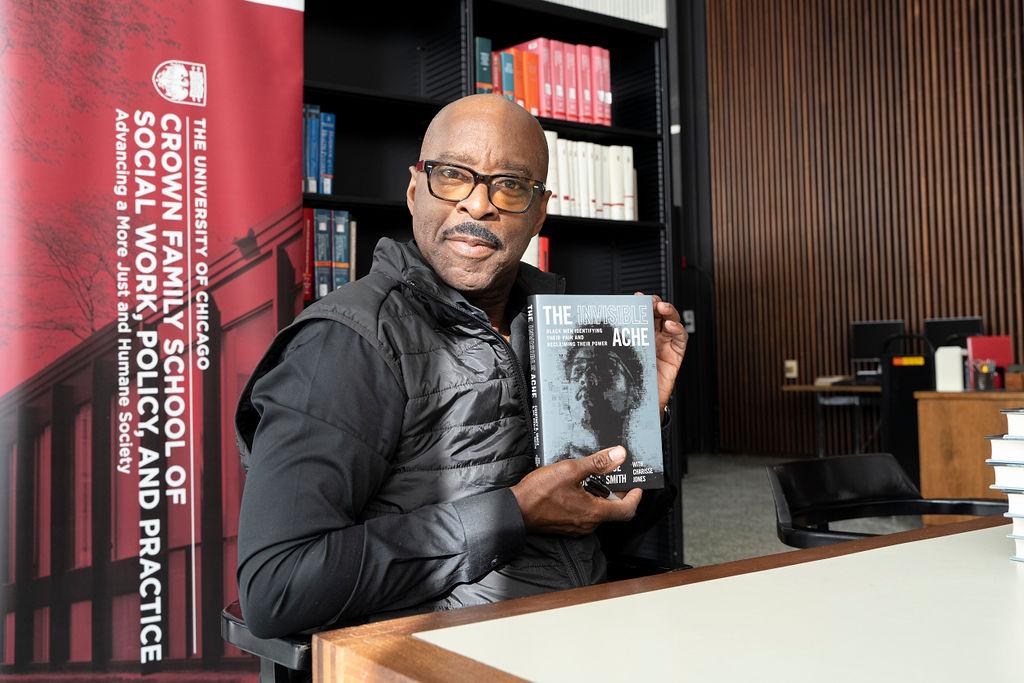

As the Pastora San Juan Cafferty Keynote Speaker, Vance discussed his own experiences, further detailed in his book, The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain and Reclaiming Their Power, co-authored with psychologist and ordained minister Robin L. Smith. The text explores suicide among Black males, drawing on his personal experiences, having lost his father and godson to suicide.

Prior to Vance’s keynote address, the tone of the event was set by Waldo E. Johnson Jr., Vice Provost for Diversity and Inclusion and Professor at the Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice. After an introduction by Deborah Gorman-Smith, the Dean and Emily Klein Gidwitz Professor of the Crown Family School, Johnson spoke to the lived experiences of Black males with respect to their struggle towards sustaining good mental health.

“The Invisible Ache … it's in conversation with the symposium’s focus on the intersectionality of identity, which links the social complexities inherent in reconciling the unique challenges posed when embracing race, gender, sexuality, and other, which are often contested identities among Black adolescent and adult men,” Johnson said. Before turning the mic over to Eugene Robinson, Jr., the AAAC Co-Chair and Master of Ceremonies, he pointed to his own work that has shown toxic masculinity exerts a heavy toll on the healthy development of Black male identity and development wellbeing. This echoed the theme of the symposium, which focused on how to break down barriers, deconstruct cultural stigmas, and improve equity and access to Black men’s mental health and wellness. Those discussions would continue beyond the keynote and into breakout sessions, workshops, and a panel.

Robinson, also the Director of Student Engagement within the Office of Student Support and Engagement at Chicago Public Schools, encouraged the audience to consider the day’s conversation as part of their own mental health journey, acknowledging the loss of family in his own life before introducing Vance and Janelle R. Goodwill, the Neubauer Family Assistant Professor, for their discussion: “I am asking you all to bring a little of yourself into this space, as I've done for you this morning,” Robinson said.

Throughout his talk, Vance spoke from a place of experience, not expertise. “First of all, I'm the poster child for not knowing what to do,” he said. “That's why we wrote the book, because people shouldn't have to reinvent the wheel.”

Goodwill, the Neubauer Family Assistant Professor and an emerging Black female scholar who examines suicide within the African American community, offered a brief description of the book. The Invisible Ache, Goodwill explained, was written to speak directly to Black men who might be experiencing some challenges with their mental health. The book opens with the lives and then suicides of Vance’s father and godson, then moves into Vance’s experience with beginning therapy at age 30.

“I was raised in a household where we were about God and achievement,” Vance recalled. “That's how we dealt with things.” But when his father died, his mother insisted he and his sister seek out a therapist — as she would as well.

Vance said it took him seeing seven or eight different therapists before he found the right fit. He expected to work with someone similar to him — perhaps someone who looked like him, had the same religion — but instead found the kindness he needed in a small, female Jewish therapist. “When I met Dr. K, when I shook her hand, I knew I was home,” he said. “I sat down and I started talking a mile a minute and I talked for 20 minutes straight without breathing. And Dr. K said, ‘Courtney, you don't have to tell me everything today.’ But I had never been in therapy before and never knew I needed to talk to someone. And then I started to realize that this is my time, and this is my space.”

Vance described his journey with therapy, which also included the ways in which he interacted with his wife and setting aside his preconceived notions of what being a husband meant and the expectations he put on his partner. When he focused on what he could do for his family, his wife did the same — and he says they now almost compete to help the other person and support them: “Once you start to do for other people, they turn around and say, ‘What can I do for you?’”

The keynote ended with Vance reading an excerpt from the book: “I want to let those in so much emotional pain that they're contemplating taking their own lives know that we've all had moments of utter despair,” he read. “But if we just hold them, if they go to a therapist, see a doctor about medication, talk to a friend, call up a religious leader, they can get through it … and just have the opportunity to sit and gaze at one more sunset, they will be glad they did.”