Improving Multisystem Collaboration for Crossover Youth

By Savannah (Sav) Felix

From the 2016 issue of Advocates' Forum

IMPROVING MULTISYSTEM COLLABORATION FOR CROSSOVER YOUTH

Abstract

This article explores the understudied population of youth who interact with both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. It argues that policy makers and practitioners should begin to use research to take on the challenge of altering the negative outcomes for these vulnerable youth. This article provides an overview of the current policies that impact this population and provides evidence in support of an improved policy approach that focuses on system collaboration as well as the expansion of federal Title IV-E and Title IV-B funding and reauthorization of key legislation.

Over the last twenty years, the child welfare field has slowly acknowledged the small population of vulnerable youth impacted by both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. This population has unique paths and positions in multiple systems, as well as strikingly negative outcomes. These youth are commonly referred to,among other terms, as “crossover” youth. The term “crossover” youth has been defined as a broad category of youth who have been maltreated and involved with the juvenile justice system at some point in their lives (Herz, Ryan, & Bilchik, 2010). These youth include those involved in the child welfare system and then the juvenile justice system; those who have a history with the child welfare system but no current involvement at the point when they enter the juvenile justice system; children who experience maltreatment but have no formal contact with the child welfare system and then enter the juvenile justice system; and youth who are involved in the juvenile justice system when they enter the child welfare system. This article provides an overview of the current policies that impact this population. It then provides evidence in support of a new policy approach to improve system collaboration. The fundamental goal of the article is to increase attention to the issues facing crossover youth, provide an overview of the current state of policy impacting this population, and offer a new policy approach to improve system collaboration and outcomes for youth. It is imperative that policy makers and practitioners use this research to take on the challenge of altering the negative outcomes for crossover youth.

OBSTACLES FACING CROSSOVER YOUTH

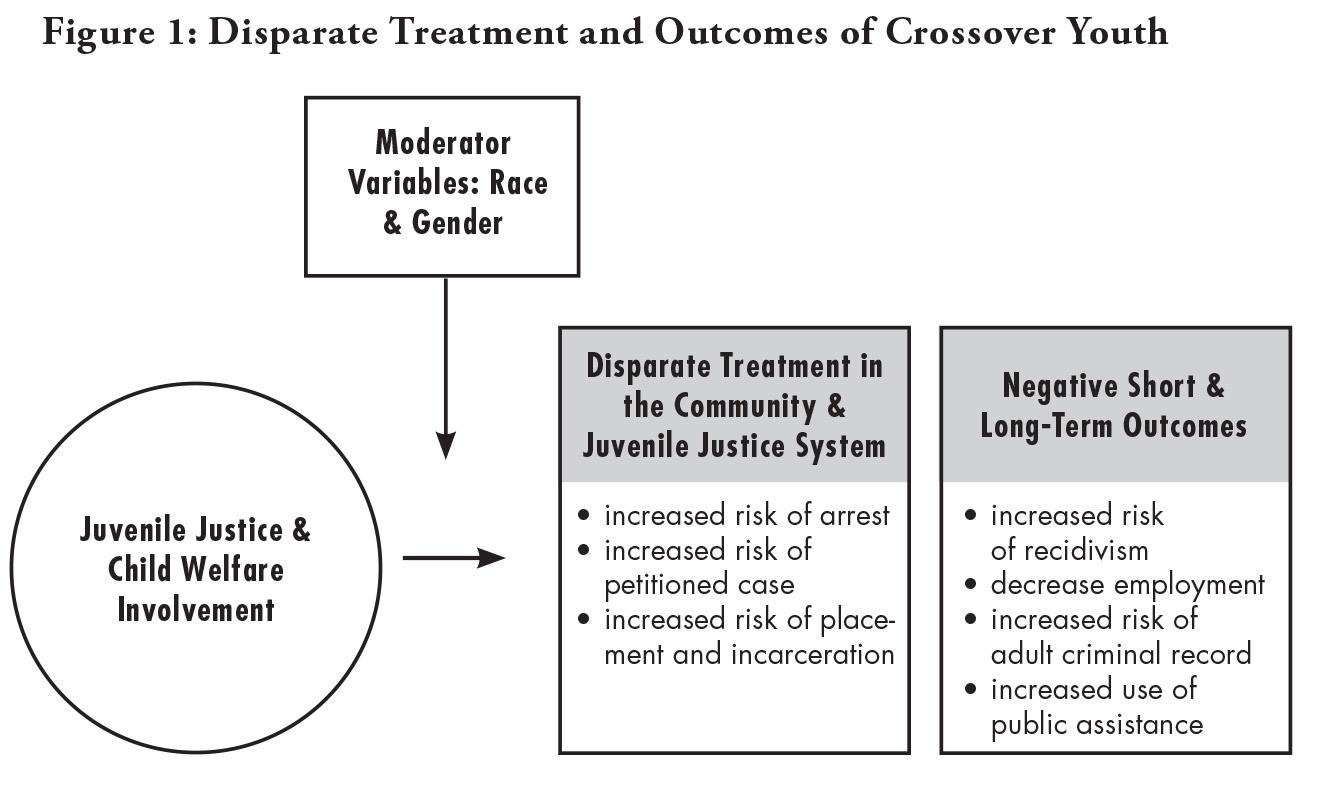

Maltreated youth are disproportionately involved in and receive disparatetreatment from the juvenile justice system (see Figure 1). Due to differences in defining crossover youth, there is varying data on the prevalence of crossover youth in the juvenile justice system. Recently, Halemba and Siegel (2011) found that 67% of juvenile justice cases in King County, Washington had some form of history with the child welfare system. When self-report data is used, prevalence rates for crossover youth increase to 79% (Kelley, Thornberry, & Smith, 1997; Herz & Ryan, 2008). On average, maltreated youth are 47% more likely than their peers to become involved in the juvenile justice system (Ryan & Testa, 2005). In part, the overrepresentation of crossover youth is due to their increased risk of arrest and case petition. Arrest rates for maltreated youth range from 13.9% to 21.6% as compared to 3.6% among the general population of youth (Widom, 2003; National Center for Juvenile Justice, 2014). In Los Angeles, 79% of crossover youth arrests occurred at Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) placements, 40% of which were group homes (Herz & Ryan, 2008). Crossover youth’s cases are also more likely to be petitioned by the court than those of non-crossover youth. In 1999, the petition rate for crossover youth was 57% greater than for noncrossover youth (Ryan & Testa, 2005).

Once they are adjudicated and formally enter the system, crossoveryouth face harsher court outcomes. Even when controlling for race, gender, and offense, crossover youth are more likely to be removed from their homes or detained. In Los Angeles County, the probability of receiving probation rather than placement or corrections was only 58% for DCFS involved youth as compared to 73% for non-DCFS involved youth (Herz& Ryan, 2008). In a study of pre-adjudicated youth in New York City, Conger and Ross (2001) found that the probability of detention for crossover youth was 10% higher than for their peers. The higher risk of harsher outcomes is also evidenced by the prevalence rates of crossover youth at the deep end of the system. Up to 42% of youth in placement have had involvement with both systems (Halemba, Siegel, Lord, & Zawacki, 2004).

The overrepresentation of crossover youth in the juvenile justice system has also been shown to contribute to disproportionate minority contact with the juvenile justice system as well as the significant increase in the female population of justice-involved youth. As compared to their white counterparts, African American youth in the child welfare system are two times more likely to be arrested at least once (Ryan & Testa, 2005). In fact, African American youth make up only 30% of the child welfare population but comprise 54% of the child welfare population that intersects with the juvenile justice system (Herz & Ryan, 2008). Ryan, Herz, Hernandez, and Marshall (2007), in a study of youth in Los Angeles County, found that open child welfare cases account for 14% of all African American youth entering the juvenile justice system. The child welfare system has also become a major pathway for females to enter the juvenile justice system. Females are the fastest growing population of justice-involved youth. Though the crossover population consists of more males than females, the child welfare system is the largest referral source for females to the juvenile justice system (Ryan et al., 2007). In fact, females make up 33% of the crossover youth population while only 26% of juvenile justice entrants from other referral sources are female (Herz & Ryan, 2008).

The crossover population’s disparate treatment is made more difficult by their intensive needs. Crossover youth are more likely to come from challenging familial circumstances and are more likely to be younger at first entry into the juvenile justice system. They are also more likely to suffer from substance abuse, have mental health issues, and face educational difficulties. In a study of crossover youth from Arizona, Herz and Ryan (2008) found that 80% of crossover youth had substance abuse issues and 61% had mental health issues, while 70% had witnessed domestic violence, 55% had an incarcerated parent, 78% had a parent with a history of substance abuse, and 31% had a parent with a history of mental illness. Female crossover youth are more likely to face gender specific challenges. In particular, they are more likely to become pregnant than their peers in the juvenile justice system only.

Challenges faced by crossover youth are often not met with collaborative solutions across systems. In transitioning between systems, crossover youth face service interruptions when they become ineligible for system-specific mental health, substance abuse, and educational services. Due to their increased risk of out-of-home placement and incarceration, crossover youth are less likely to receive appropriate treatment services (Pumariega et al., 1999). For female crossover youth, who are at greater risk of pregnancy, there are few gender-specific programs that address their needs.

Given their risk factors, disparate treatment, and barriers to appropriate services, it is not surprising that crossover youth tend to have poorer short-term and long-term outcomes. In the short term, crossover youth are more likely to recidivate. In King County, Washington, within six months, 42% of crossover youth recidivated as compared to 17% of youth with no history of involvement in the child welfare system (Halemb & Siegel, 2011). Within 24 months, 70% of crossover youth recidivated as compared to 34% of youth with no history of involvement in the child welfare system (Halemba & Siegel, 2011). In the long-term, crossover youth face barriers to successful adulthood transitions. For example, when comparing outcomes of youth involved in the child welfare system only, the probation system only, and both systems, Culhane et al. (2011) found that crossover youth between the ages of 22 and 26 were more likely to be on public welfare, less likely to be employed, and more likely to have an adult criminal record. In fact, maltreatment increases the likelihood of arrest as an adult by 28% (Widom & Maxfield, 2001).

Not only do the experiences and outcomes of crossover youth impact the life prospects of youth, but they also increase the public burden. As recidivism and out-of-home placement increases, so do the costs of services. It has been estimated that placement costs for one crossover youth are between $35,171 and $38,000 (Culhane et al., 2011; Halemba et al., 2011). In addition, the lack of coordination in funding and operations across systems means that significant resources are wasted on duplicative and contradictory assessments, planning, management, and services. Furthermore, the deeper crossover youth go in the system, the less effective and more expensive their treatment becomes.

Clearly, the disparate impact faced by crossover youth, disproportionality of contact by race and gender, poor short-term and long-term outcomes, and costs to society provide evidence that there is a need for a policy focus on the issue of crossover youth.

CURRENT POLICY ADDRESSING CROSSOVER YOUTH

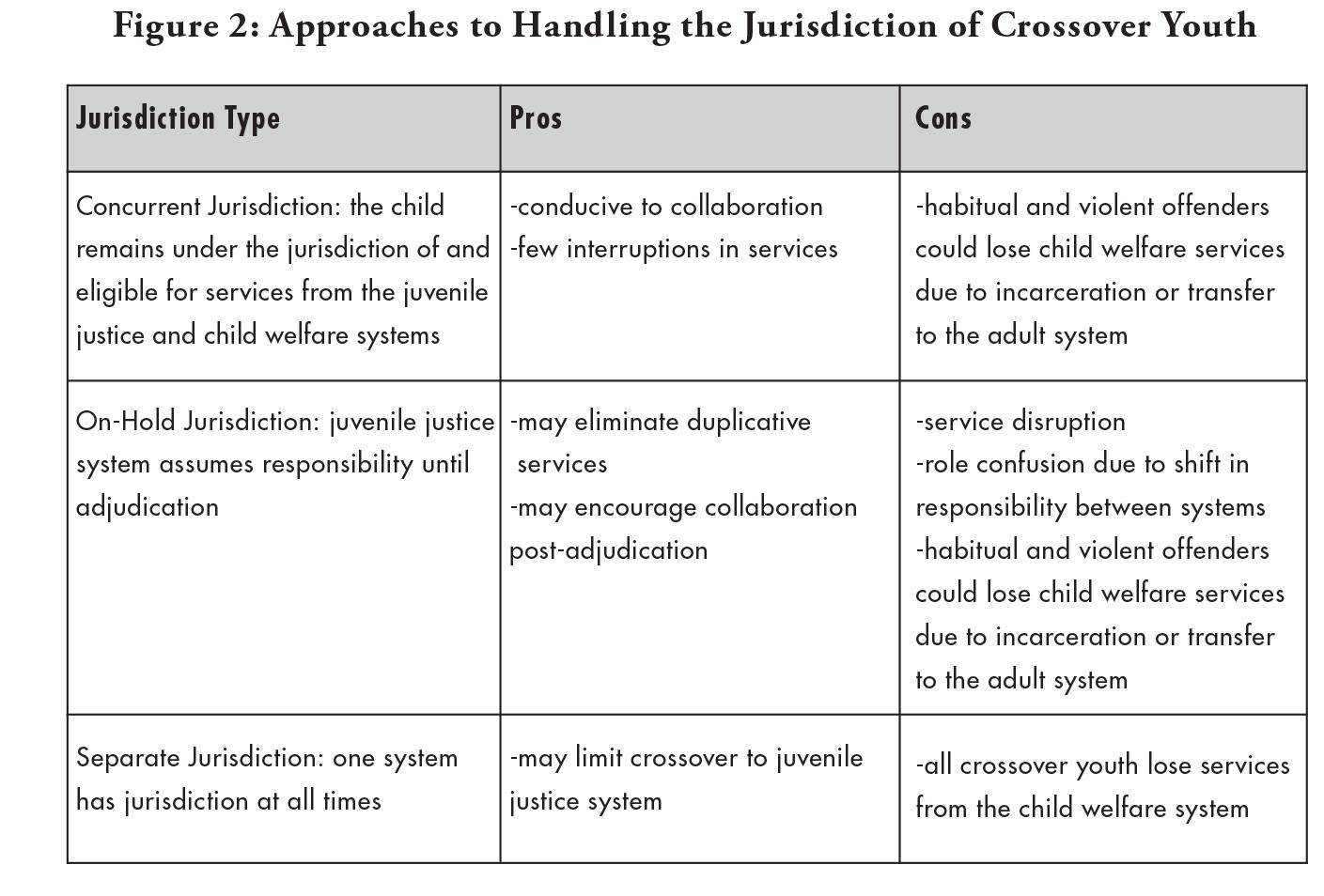

Crossover youth straddle two systems with conflicting missions. The child welfare system seeks to protect them and provide victim-focused services. The juvenile justice system aims to “rehabilitate” and provide perpetrator focused services. Bridging these two systems creates many challenges for states. Currently, individual state policies dictate protocol for handling crossover youth. There are three statutory approaches to handling the jurisdiction of crossover youth: concurrent jurisdiction, “on-hold” jurisdiction, and separate jurisdiction (see Figure 2).

Concurrent jurisdiction means that youth remain under both jurisdictions. Typically, one system has primary responsibility for the youth, but they continue to receive services from both. A benefit to concurrent jurisdiction is that it is possible for most youth to remain in their placement, retain services, and receive integrated case planning. Concurrent jurisdiction is also more conducive to system collaboration. A downside to concurrent jurisdiction is that incarceration or transfer to adult court could result in termination from the child welfare system, causing habitual and violent offenders to lose access to critical services. In addition, though concurrent jurisdiction encourages collaboration, effective collaboration is rare.

“On-hold” jurisdiction means that there is a temporary break in child welfare system services as the juvenile justice system assumes responsibility for the youth up until adjudication. After disposition, if it is determined that the youth will enter institutional corrections, the youth will no longer receive services from the child welfare system. When juvenile justice system involvement ends, youth are able to return to their suitable child welfare placements. If it is determined at disposition that the youth will receive community alternatives, the youth will remain in the child welfare system. A benefit to this approach is that it may eliminate duplicative services. Further, after disposition, it allows most crossover youth to receive collaborative services. The weaknesses of this approach are that youth experience service disruption, and habitual and serious offenders may lose access to all collaborative services. Furthermore, inevitably, some youth fall through the cracks due to confusion over roles as responsibility shifts between systems.

Lastly, separate jurisdiction requires that the youth be a part of a single system. Therefore, if a youth is adjudicated in the juvenile justice system, that youth will be terminated from the care of the child welfare system. The benefit of this approach is that there is often a preference for youth to remain in the child welfare system, thus limiting the number of youth that crossover to the juvenile justice system. However, this approach also has many disadvantages that tend to negatively impact the most vulnerable youth. Youth that do crossover to the juvenile justice system lose all of the benefits of the child welfare system: placement, treatment, attorneys, advocates, social workers, and other targeted services.

On the federal level, legislation that addresses the needs of crossover youth is limited, but has begun to expand. In 2010, Congress reauthorized the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) for 5 additional years. The intent of CAPTA is to continue to improve the child welfare system. In the reauthorization, additional language was added to provide funding for states to improve data collection on this population as well as collaborative services for youth involved in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems through research, programming, and demonstrations. The language of the act indicates that funds should be used to focus on:

"Effective approaches to interagency collaboration between the child protection system and the juvenile justice system that improve the delivery of services and treatment, including methods for continuity of treatment plan and services as children transition between systems" (Child AbusePrevention and Treatment Act, 2010, p. 10).

In addition, the act requires that states provide a report that indicates the number of youth involved in both systems.

There are several strengths to the 2010 reauthorization of CAPTA. First, it brings awareness to the issue of crossover youth. Second, it encourages multisystem collaboration. In particular, it asks states to begin to develop methods to improve treatment planning and case management processes between systems. Third, it requires the collection of data on the prevalence of crossover youth. There is limited data in the literature on how many youth are impacted by both systems; therefore, this requirement will fill an important gap. Finally, CAPTA provides states with much needed funding to begin to meet the requirements of the act. However, CAPTA overlooks key areas that need to be addressed. First, it does not address the issue of information sharing. A major challenge to multisystem collaboration has been the limited guidance on how information should be shared. Second, it does not require the collection of prevention-focused data. Currently, the only data requirement is that states provide the number of crossover youth. In order to begin to understand the factors that increase the likelihood of dual involvement and lower prevalence, it is important that states begin to capture data on characteristics of crossover youth. CAPTA is due for reauthorization in 2016.

In addition to CAPTA, the 2002 Congressional reauthorization of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJPDA) is relevant. The act ran out in 2007 and remains overdue for reauthorization. The intent of JJDPA was to improve the juvenile justice system. In its 2002 reauthorization, language was added to require that states receiving formula grants begin to collaborate with the child welfare system by implementing record sharing policies and systems and providing continued child welfare services to youth that crossover. The Act reads in part:

"Not later than 1 year after the date of enactment of this paragraph, the Administrator shall conduct a study with respect to juveniles who, prior to placement in the juvenile justice system, were under the care or custody of the State child welfare system, and to juveniles who are unable to return to their family after completing their disposition in the juvenile justice system and who remain wards of the State. Such study shall include–the number of juveniles in each category; the extent to which State juvenile justice systems and child welfare systems are coordinating services and treatment for such juveniles; the Federal and local sources of funds used for placements and post-placement services; barriers faced by State in providing services to these juveniles; the types of post-placement services used; the frequency of case plans and case plan reviews; and the extent to which case plans identify and address permanency and placement barriers and treatment plans" (Library of Congress, 2002).

There are several strengths to the reauthorization. First, it requires the collection and use of child welfare data. As has been discussed, it is imperative that states begin to understand the characteristics and needs of the crossover population. This data can be used to improve decision making and service provision for crossover youth. Second, it requires the protection of the rights of eligible crossover youth to case plans and case plan review. This allows crossover youth to maintain some of their rights as former Title IV-E eligible foster youth. Third, it requires states to conduct research on the crossover population that can improve understanding of the population’s experiences and needs. Despite these strengths, the reauthorization has several weaknesses. First, it does not require the sharing of juvenile justice data. While it is important that the incorporation of child welfare data is specified, it is also important that information sharing is reciprocated. Second, though the act requires that eligible crossover youth be entitled to case plans and case plan reviews, it does not require that foster care services continue. This may cause a gap in or lack of services for crossover youth when they return to the community. Lastly, it does not address collaboration for youth exiting the juvenile justice system and entering the child welfare system.

While CAPTA and JJDPA provide important guidance to the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, federal policy has yet to provide appropriate incentive structures to encourage states to enforce multisystem collaboration. In part, this is due to the lack of a uniform definition for the crossover population, contradictory goals and outcomes, and the absence of information and data sharing systems. This may be due to separate funding and operational structures. Currently, Title IV-E and Title IV-B prohibit reimbursement funds for youth involved in the juvenile justice system.

AN INTEGRATED POLICY APPROACH FOR MULTISYSTEM COLLABORATION

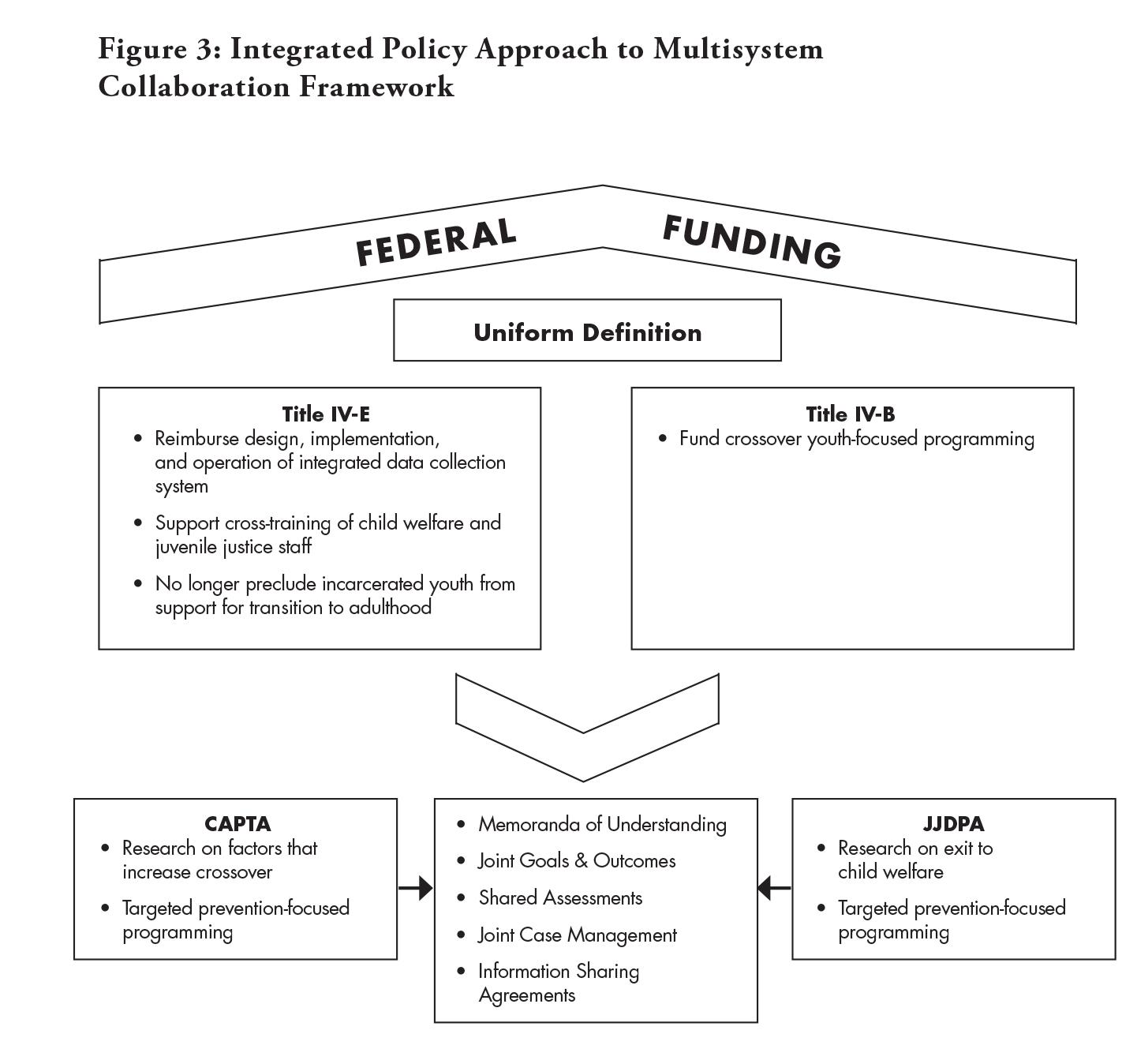

Based on the need to address issues surrounding crossover youth and the weaknesses of current policy attempting to address the issue, it is recommended that a new approach be taken to improve system collaboration. The recommendation is an expansion of federal Title IV-E and Title IV-B funding, as well as reauthorization and amendment of JJDPA and CAPTA (see Figure 3).

The first step to the approach is to increase federal funding to support crossover youth by expanding Title IV-E and Title IV-B so as to include reimbursement for crossover youth. Not only will this establish a shared funding stream but also a fiscal incentive for states to pursue collaboration. In order to prevent confusion, it will be important to establish a uniform definition of the population that will be supported by this funding. It will also be important to encourage states to use a concurrent jurisdiction model since it is the most conducive to system collaboration and continuity of services. In expanding Title IV-E, it is recommended that states be reimbursed for design, implementation, and operation of integrated data collection systems. In order to address the absence of information and data sharing systems, Title IV-E reimbursement would provide states with incentives to develop integrated data collection systems between the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. This infrastructure will ideally support coordination and communication across systems. States should also receive Title IV-E funding for training staff on policies, practices, and expectations of both the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system, the characteristics and needs of crossover youth, and best practices for collaboration.

A further expansion of Title IV-E might end the exclusion of transition to adulthood services for incarcerated youth. Crossover youth exiting the juvenile justice system post-incarceration are vulnerable to recidivism, unemployment, and homelessness. Without access to the transitional housing, employment services, scholarship programs, mentors, and mental health resources provided to former foster youth, these youth face significant challenges (Wylie, 2014). The expansion of Title IV-B could support programming that addresses the risks faced by crossover youth. Currently, there are few programs targeted toward the crossover population and funding could encourage states to support the development and expansion of promising programs.

The second step to the approach is to reauthorize and amend both CAPTA and JJPDA. In amending CAPTA, states should be asked to focus on research aimed at understanding the mechanisms that contribute to the moving of a child from the child welfare system to the juvenile justice system. This research should inform the development, evaluation, and support of prevention-focused programming aimed at preventing crossover. Further, a critical aim of the research should be to address disproportionality by race and gender in crossing between the two systems.

In amending JJPDA, states should be asked to focus on research aimed at understanding the factors involved in moving a child from the juvenile justice system to the child welfare system. In Illinois, it was found that 10% of all youth exiting the juvenile justice system enter foster care within one year (Cusick, George, & Bell, 2009), yet little is known about this population. This research should inform programming such that programs aimed at preventing crossover are developed, evaluated, and supported. Both acts should include clear directives regarding collaboration across systems to provide appropriate and uninterrupted services. They should also continue to be reviewed and assessed for future amendment.

In taking the two-pronged approach that creates shared funding streams to support collaboration across systems and legislation that funds prevention efforts within systems, states are not only incentivized to improve their prevention efforts but also to increase collaboration across systems. It is expected that collaboration will result in Memoranda of Understanding, joint goals and outcomes, shared assessments, joint case management, and information sharing agreements.

CONCLUSION

This paper attempted to provide evidence for the need for increased attention on the issues facing crossover youth, an overview of the current state of policy impacting this population, and a new policy approach to improve system collaboration and outcomes for crossover youth. Due to the disparate impact faced by crossover youth, disproportionality of contact by race and gender, poor short-term and long-term outcomes, and costs to society, it is clear that there is a need for a policy focus on the issue of crossover youth. Though there are strengths to current policy that address issues facing crossover youth, there are too many weaknesses and too few efforts by states to establish multisystem collaborations. A two pronged approach that focuses on expanding federal Title IV-E and Title IV-B funding as well as reauthorizing and amending JJDPA and CAPTA is recommended as an initial strategy approach to increase multisystem collaboration and improve outcomes for crossover youth.

REFERENCES

Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act. (2010). S.3817 – 111th Congress. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/capta2010.pdf

Conger, P., & Ross, T. (2001). Reducing the foster care bias in juvenile detention decisions: The impact of project confirm. New York, NY: Administration for Children’s Services, The Vera Institute of Justice.

Culhane, D. P., Byrne, T., Metraux, S., Moreno, M., Toros, H., & Stevens, M. (2011). Young adult outcomes of youth exiting dependent or delinquent care in

Los Angeles County. Retrieved from http://www.ncjj.org/Publication/Doorwaysto-Delinquency-Multi-System-Involvement-of-Delinquent-Youth-in-King-County-Seattle-WA.aspx

Cusick, G. R., George, R. M., & Bell, K. C. (2009). From corrections to community: The juvenile reentry experience as characterized by multiple systems involvement. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

Halemba, G. J., Siegel, G., Lord, R. D., & Zawacki, S. (2004). Arizona dual jurisdictionstudy: Final report. Pittsburg, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Halemba, G. J., & Siegel, G. (2011). Doorways to delinquency: Multi-system involvement of delinquent youth in King County (Seattle, WA). Pittsburgh: National Center forJuvenile Justice.

Herz, D., & Ryan, J. P. (2008). Building multisystem approaches in child welfare and juvenile justice. Washington, DC: Center for Juvenile Justice Reform.

Herz, D. C., Ryan, J. P., & Bilchik, S. (2010). Challenges facing crossover youth: An examination of juvenile justice decision making and recidivism. Family Court Review, 48(2), 305-321.

Kelley, B. T., Thornberry, T., & Smith, C. (1997). In the wake of child maltreatment. OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Library of Congress. (2002). Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 2002. Retrieved from: http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/cpquery/&dbname=cp107&sid=c p107xndpP&refer=&r_n=hr685.107&item=&sel=TOC_693185&

National Center for Juvenile Justice. (2014). Juvenile offenders and victims: 2014 national report. Retrieved from http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/nr2014/downloads/NR2014.pdf

Pumariega, A. J., Atkins, D. L., Rogers, K., Montgomery, L., Nybro, C., Caesar, R., & Millus, D. (1999). Mental health and incarcerated youth: Service utilization. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 8(2), 205-215.

Ryan, J. P., & Testa, M. K. (2005). Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 227-249.

Ryan, J. P., Herz, D., Hernandez, P., & Marshall, J. (2007). Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating child welfare bias in juvenile justice processing. Children and Youth Services Review, 29, 1035-1050.

Widom, C. S., & Maxfield, M. G. (2001). An update on the “cycle of violence.” Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/184894.pdf

Widom, C. S. (2003). Understanding child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: The research. In J. Wiig and C. S. Widom with J. Tuell (Eds.), Understanding child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: From research to effective program, practice, and systemic solutions (pp. 1-10). Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America Press.

Wylie, L. (2014). Closing the crossover gap: Amending Fostering Connections to provide independent living services for foster youth who crossover to the justice system. Family Court Review, 52, 298-315.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SAVANNAH (SAV) FELIX is a second-year clinical student at the School of Social Service Administration. Prior to coming to SSA, Sav was an assistant director at The Choice Program at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, which provides community-based, family-centered case management approach to delinquency prevention and youth development. Sav currently works as a clinical social work intern at Cook County Juvenile Court Probation, where Sav provides services to court-referred youth and their families. At SSA, Sav is a research assistant for Professor Curtis McMillen. Sav holds a B.A. in economics from the University of Chicago.